Osseointegration Is a Beneficial Solution for Amputees

Author: Lisa K. Cannada, MD, FAAOS

Category: Clinical

Date: May 2021

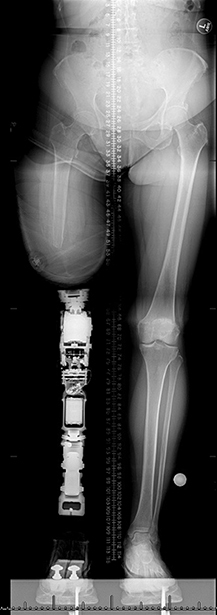

In December 2020, the FDA approved the Osseoanchored Prostheses for the Rehabilitation of Amputees (OPRA) Implant System—the first implant system in the United States for transfemoral amputees who have difficulty using a conventional prosthesis. OPRA had been previously available and marketed under a humanitarian device exemption (HDE) since 2015.

With new treatments comes the need for experts in the technique. Lisa K. Cannada, MD, FAAOS, spoke with a U.S. pioneer in this technique: Jason Stoneback, MD, FAAOS, associate professor in the Department of Orthopedics at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, as well as vice chair of clinical affairs, chief of orthopaedic trauma and fracture surgery, and director of the Multidisciplinary Limb Restoration Program at the University of Colorado Hospital. He has been featured on “CBS Sunday Morning” and received the University of Colorado Pioneer Award 2021 for his work on this technique.

Dr. Stoneback: OI in amputees has its origins in dental implant technology. Per-Ingvar Brånemark, MD, PhD, a Swedish physician, discovered the ability for titanium implants to osseointegrate into bone. This finding led to the development of titanium screw fixation devices buried into the mandible. Once the implants osseointegrated into the mandible, a prosthetic tooth was then attached, giving the patient a functional tooth. Dr. Brånemark’s son, Rickard Brånemark, MD, PhD, then took this screw fixation technique and applied it in amputees. Shortly after the use of screw fixation implants in amputees was established, a press-fit technique and implant design were developed by Horst Aschoff, MD, PhD, in Germany. The press-fit technique utilizes the same technology and similar technique as a press-fit total hip arthroplasty.

What took so long for the FDA approval to happen?

The OPRA device has been under HDE for transfemoral patients since 2015 and just recently achieved full market approval. With the high risk of infection and potential for complications, a lot of data had to be pulled from all around the world to satisfy the FDA’s requirements to transition from an HDE to full market approval. The next step will be achieving full market approval with press-fit-type devices, which are currently only available in custom implant options.

Can you discuss the differences between OPRA and a press-fit OI bone-anchored prosthesis (BAP) technique?

There are significant differences between the two, beginning with the surgical technique, the rehabilitation, and finishing with the time to ambulation.

The OPRA BAP is a screw fixation system done in two surgical procedures, with the first one being the less intensive. In the first procedure, the fixture is implanted into the residual limb bone. Approximately six months later, a second, more intensive surgery is performed to attach additional components to the fixture, and the main portion of the surgical procedure is the soft-tissue portion, ending with a full-thickness skin graft overlying the distal femur. The patient is hospitalized for about five to seven days, and then it takes six weeks to begin prosthetic wear. It begins with a shorter prosthesis, progressing to a longer prosthesis with about four weeks in each prosthesis and limiting to axial loading only. The total time to walking prosthetic use with OPRA is approximately 9.5 months.

A press-fit BAP also has two stages of surgery (although sometimes done in a single stage). The first stage is the more intensive surgery in this case, where the implant is placed and the soft tissue is rearranged. The second stage occurs about six weeks later and is mainly creating the stoma, which is done as an outpatient procedure. The patient can begin walking in the prosthesis approximately 48 hours after the second stage.

These procedures are becoming more popular throughout the world and now in the United States. How did you learn about becoming proficient in the procedure, as it was not around when you did training?

I spent a lot of time in Europe learning the techniques and developing relationships with OI surgeons and teams around the world. These relationships have been incredibly rewarding and have been one of the highlights of my career. When I first started doing these procedures, the European surgeons came over for cases. It has now come full circle, as surgeons now come to learn from me and our institution’s experience.

Who is the ideal patient for OI?

The ideal OI patient has had an amputation either from trauma or tumor and has trialed sockets without success. Typical problems with traditional socket use are volume fluctuations of the residual limb causing the prosthesis to fit poorly throughout the day, wound breakdown, pain, and discomfort with daily use. Patients who are experiencing these socket-related problems and have goals of improving activities of daily living and daily comfort make the best candidates for OI.

Most patients will tell you that this is a profoundly life-altering procedure. They are able to sit at a table without having a large socket underneath their leg, that if present makes it very uncomfortable to just enjoy dinner with friends and family. They don’t have to worry about the prosthesis falling off at an inconvenient time, causing them to fall, and also no longer have to deal with wound breakdown or abrasion from the socket. Speed of walking, normalization of gait patterns, and decreased oxygen consumption are all benefits of OI. Finally, there is the phenomenon of osseoperception, which allows an amputee to actually feel how much force they’re putting through the prosthetic limb; a person can feel the difference between uneven ground and where the prosthetic limb is in space. This change vastly improves walking confidence and decreases risk of falls.

This technique represents an exciting option for patients. Yet with any procedure, complications can occur. What are the complications of OI?

Complications of OI can vary from stoma/skin penetration to site pain to soft-tissue infection. Infections can often be handled with simple topical triple-antibiotic cream or may require a short course of oral antibiotics.

More severe infections may require surgical debridement with intravenous antibiotics to retain the implant. One of the most severe complications is septic or aseptic loosening of the implant requiring explantation. Periprosthetic fracture is always a concern, especially in a patient who has been an amputee for a long period of time and may have significant bone mineral density loss from not loading the residual limb.

Success with OI requires a team. Who is the team you need to make OI a success?

Support staff includes prosthetists, physical therapists, and psychological support. For OI to be successful, it takes a tremendous amount of support and a multidisciplinary team. Our program has support from physical medicine and rehabilitation physicians, prosthetists, athletic trainers, nurse practitioners, nurse navigators, and plastic surgery, vascular surgery, physical therapy, psychology, and infectious disease specialists. I can’t stress how important this multidisciplinary team is for a successful outcome for osseointegrated patients.

What are the activity restrictions for patients who undergo OI?

The patients can enjoy a range of athletic activities, including snowboarding, swimming in the ocean and pools (just taking precautions to avoid stagnant water and hot tubs), and they can even enjoy a Peloton or similar machine.

What has been your experience with OI?

I have performed more than 30 cases. Most were transfemoral followed by transtibial, and most were due to trauma. However, I also do this for patients with cancer and for other reasons that have resulted in limb loss.

How did it feel to receive the University of Colorado Pioneer Award?

I received that for my work on developing the OI program and bringing OI to the University of Colorado. I began the Limb Restoration Program in 2015 due to my interests in limb salvage. This program provides multiple services and options, including Ilizarov and hexapod ring fixators, limb lengthening, treatments for nonunions infections, and bone transport procedures. Amputation and the use of OI fit right in.

Although my name is on the award, the award truly belongs to our multidisciplinary team, who spent years developing the program into what it is today.

Lisa K. Cannada, MD, FAAOS, is a member of the AAOS Now Editorial Board, lead of the AAOS Now Diversity Content Workgroup, and an orthopaedic trauma surgeon living in Jacksonville, Fla. She is affiliated with the Hughston Clinic and Novant Health.